Hi, I am Ashutosh, a security researcher with specialization in application security, VAPT, and Purple teaming. I have worked for a Big 4 firm where I conducted security assessments for multiple Fortune 500 clients.

In my free time, I hunt for vulnerabilities in some of the largest companies’ systems through bug bounty programs. I have reported issues to NASA, Coinbase, Google, US Dept. of Defense, and some major airlines. Apart from finance and crypto, I have always been interested in working in aviation security.

On a Saturday afternoon, I targeted a major global airline with an active bug bounty program and 50M+ annual passengers, a story I later shared during my talk at the ET-CISO Annual Conclave, with 100+ CISOs in the audience.

[Disclaimer – Featured image is for representation purposes only.]

Ok, let’s start..

Airlines are an interesting target as they collect critical information from passengers such as their names, Emails, Phone numbers, birthdates, passport details, frequent flyer numbers, travel history, and booking info. Even luggage items. Fun fact: If the airline finds something unusual in your luggage, they make a note of it. [Don’t ask me how I know ;)]

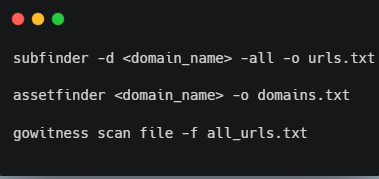

At ~12:20 PM, I started with routine recon work, explored their internet-facing infrastructure, and enumerated subdomains using subfinder (command: subfinder -d <domain_name> -all), assetfinder (command: assetfinder <domain_name> > domains.txt), etc. Then I grabbed screenshots of each web application/URLs owned by the airline using gowitness (command: gowitness scan file -f all_urls.txt). My goal was to find PII leaks, so I had to find a feature that gave information about passengers or their bookings.

The good thing about airline/travel websites is they want to make it easy for passengers to access their travel info. It’s not some net banking application, so you don’t see 2FA implemented on such websites because of the business case.

I stumbled upon a page which required a last name and some booking code to view booking info. That code was alphanumeric and random (something like a PNR, Passenger Name Record), so there was no point in bruteforcing that. I explored other pages and found another feature for checking refunds which asked for a last name and a reference number.

The problem was I never traveled using this airline, so I needed someone else’s details, someone who had traveled via this airline. But how do I find those users? Easy… There are always users who complain on the company’s social media handles, and some users who complain with extra information (such as their customer ID, complaint number, ticket ID, etc.). I was able to find several users’ reference numbers which I could use to obtain their information. But still, I was close but not there yet. This reference number was alphanumeric, so again, I couldn’t bruteforce that easily.

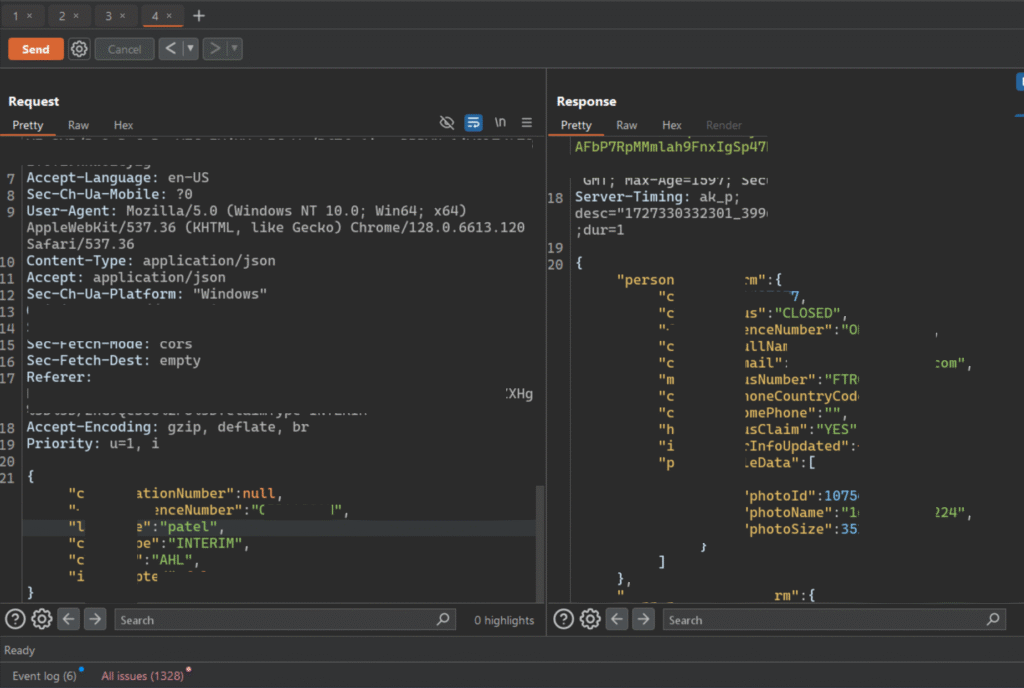

Based on the information I found from users’ complaints, I noticed that the alphanumeric reference number which I was worried about had characters, but they were not random. There was a pattern. The number involved a 3-letter IATA code for the destination airport (for example, LHR for Heathrow Airport, London), and the last character was always static. So now I only had to figure out the numbers part, which could be easily bruteforced. The HTTP request looked similar to one as shown under.

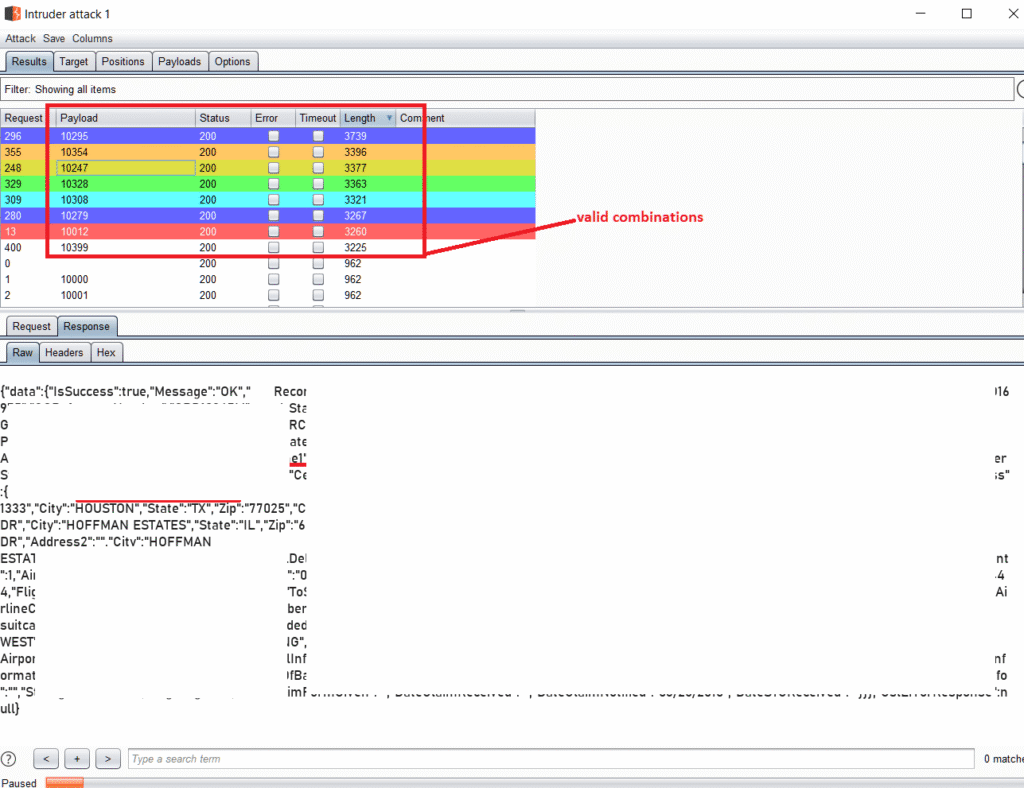

Finally, I cracked the format of the reference number. The next task was to bruteforce the integers of the reference number, hoping there was no rate limit on that endpoint. So at ~03:30 PM, I fired up Burp Suite again, sent the HTTP request to Intruder with a famous airport’s IATA code and other characters in place, and started the attack.

And… it worked! They did not implement rate limiting. No blocking, nothing!

By 04:30 PM, I validated the issue by fetching approx 10 users’ info to confirm the vulnerability and for the proof-of-concept screenshots. Based on the information I received, I was also able to modify the passengers’ upcoming trips as well. The entire thing, from initial recon to reporting, took one only few hours. The airline accepted the report, fixed the issue, and rewarded me for this finding, which was equivalent to approximately $12,000. Not bad for a Saturday afternoon.

I reported several other issues to this program and earned enough for some more international trips. If this major airline had this issue, chances are others might have similar vulnerabilities. If you’re working in aviation security or know someone who is, please share this so they can check their own systems.

If you found this writeup helpful or have thoughts to share, feel free to connect with me LinkedIn or X.

Explore my other writeups,